Nuclear semiotics for future joiners

How to craft durable warnings for your organizations + relationships

When radioactive waste is buried, it will never not be radioactive ever again, not in 100 years or 1,000 or 10,000. And while the humans who buried it know that, the humans in that theoretical far-off future would not. Their language, culture, and symbols will almost definitely be different from ours; so how would we give them the heads up to not dig a well or build a robo-hotel where this poisonous mound of earth is?

While the stakes are lower, I’d wager the shape of this challenge feels familiar for any of us attempting to fossilize a message for the future; for new volunteers joining our organizations, new members to our movements, new roommates moving into our houses, future staff to be hired after we quit or leave the board.

There will (hopefully) always be new people joining. We may be around to welcome some of them. Others we may never meet at all. How will we communicate lessons to future joiners that they might really benefit from knowing?

One answer might be: let them dig into that radioactive earth. Sort of brutal, but maybe the best way to learn a lesson is to experience the feeling of your mistake. Maybe someone telling you a lesson will never be as effective a teacher as you still trying that fraught group meeting format or arranging the chairs in a room your way and realizing you don’t have enough space or bringing together the groups of people you were told just don’t get along and watching them bicker for an hour.

But there’s something humane in wanting to help future people avoid the suffering you and others experienced, you know?

In our bike co-op, we just closed an era where we attempted a fully volunteer-run governance model. A lot of good came from the whole thing, but ultimately there were enough cracks in the structure of it – complex decisionmaking process that required a lot of skillbuilding, painful conflict as a result of those lack of skills, missing connective tissue with staff and other moving parts of the organization – that we just sunsetted the model in favor of a simpler one. Our new model is still heavily volunteer-supported, but centers clearer points of decisionmaking between staff and the volunteer board and will, if all goes well, actually lead to more voices being included in our process than before.

The lessons from this entire experience are fresh in the minds of a group of maybe 30 of us or so, a sort of cohort forged in the flames of tense meetings and consensus trainings and alternative bylaws.

But there are new people coming into the co-op every day! They did not go through the last two years of this! And every time one of them asks about volunteer decisionmaking, my entire body tenses. One time, I was 5 minutes deep in giving someone the shpiel about everything that had gone wrong in the last few months because I thought they were about to attend one of the last meetings of this volunteer group, and then they politely let me know they were there for a different meeting entirely.

The primal desire to warn people off situations that have failed you before is a noble one: Don’t tread where we have. There are snakes and 4-hour long meetings and nightmares here.

But the desperation behind that warning is likely to make us all act super weird in the process. Or at its worst: make us sound like naysayers, or downers, or as a friend and I joke when we accidentally begin sentences with “Back when I got involved here…”: it makes us sound like uncles!

When a group of artists, anthropologists, and scientists in 1990 were given the challenge of how to communicate the radioactive danger of nuclear waste buried at Waste Isolation Pilot Plant for people 10,000 years in the future, they had an interesting constraint: they couldn’t just have a freak like me whose job it was to stand at the glowing gates being like “You’re not gonna want to go in there. Oh, you want to know why? How much time have you got?”

They had to use non-verbal tactics.

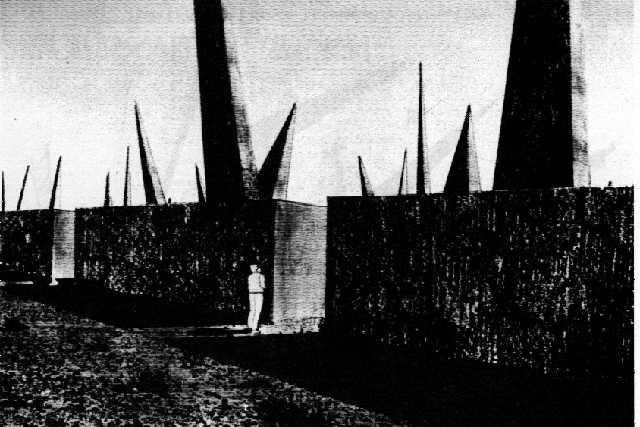

One group proposed a comic strip with a very rudimentary stick figure character opening a radioactive barrel and falling to the ground. Another suggested a symbol like a skull and crossbones. Another wanted to alter the landscape design itself, sloping the land upward with sharp and foreboding cacti or “large mounds of earth shaped like lightning bolts”. Another (the most well known for a reason) proposed we create a new breed of cat that would change colors if exposed to radiation. We would have called them ray cats!

The thing I love most about the ray cat idea is the design system around the cat itself; the warning would also be communicated through the folklore we would create about them. Songs, stories, superstitions, rituals. Even if the exact premise of the ray cat didn’t emerge intact from a 10,000 year game of telephone, its cautionary aura might.

What if the best way to create a warning message for future joiners is to embed it into culture itself?

Here are a few ways we might do that.

In shorthand

“Uh oh is this us going down the ‘Halloween Party 2022’ path again” or “let’s get one or two people definitely bringing a dish do we can avoid a May potluck situation”. Obvious drawbacks here are that this creates more insidery references, but in my experience it can create a shared mini-language over time and pique curiosity for people who have no idea what you’re talking about but want to know.

Through storytelling

On the other side of the spectrum from the above, going beyond simply saying “this didn’t work” but really spending time talking through what happened, what didn’t work about it, and why. Best conveyed through dedicated chats over coffee or breakfast or onboarding, not just as an aside in a meeting. If you’re really into this stuff, here’s a funny hierarchy of information complexity recommended from the work mentioned above.

Leaving really good archival notes

Retrospectives, exit interviews, narrative summaries or footnotes tacked onto meeting minutes that add color to decisions made. Articulating the logic and feeling behind moments in time that might not be conveyed through a simple rundown of events or milestones. See: the importance of community archiving.

Related: notes from actual humans from the past?

Like letters written to your successor or following cohort? A ritual where a departing person or group of people pass on their best advice in a huge scrapbook or shared community board or fading graffiti wall in your bathroom? I feel like there is a weight given to the advice of people transitioning out from something, a sort of holy space made for their parting thoughts, that we don’t always give to each other in present times.

Deep reflection and personal integration

Making actual time and space to integrate a narrative of an experience across a group of people makes it less likely to be distorted over time. Even if there are still a range of opinions about what happened, there is basic alignment about the important stuff. When we made the recent governance shift at the co-op, many of us spent hours on the phone and going for walks with each other to process what was happening. I hope this leads to more understanding than if a decision had been communicated in just one email thread.

Evolving values or community agreements

Community agreements are only more effective the closer to reality they actually are, and updating them to reflect recent learnings can be one more moment in a new person’s journey that brings them into our culture as it is, not as it once was.

Experience design of the thing itself

If your gatherings tend to prioritize one or two voices and this has led to understandable frustration in the past, try out formats to increase participation. If you find eager new folks steamrolling with their fresh ideas that have been tried and caused harm or stress before, build in an expectation of their own engagement in something to earn some experience before designing for others.

There’s something beautiful in the image of a long line of people passing a cumulative journal between each other that arrives at you, a new person, to ground you in all the context and learnings that came before you.

Maybe the learnings are not always on point. Maybe sometimes they come off as preachy and overconcerned and the stuff that failed once is tried again in exactly the same way and it goes better this time! Or maybe they save one person from having to make the same mistakes you did 10,000 years in the future.

This essay was obviously heavily inspired by the work of the Human Interference Task Force, which you can read more about here or listen to a nice podcast episode on here. I’m also a dummy and didn’t realize one of my favorite artists Emperor X wrote a song all about this (well, mostly about ray cats) which you can listen to here!

or simply click that ₊˚.⋆⁺₊💜₊˚.⋆⁺₊ at the top if you indeed liked it, we always appreciate that here at group hug hq!!