CPR As a Civic Responsibility

A story about a city all learning at once

💜 Heads up: in this piece there’s mention of cardiac arrest, overdose, and requiring life saving techniques

Did you know that the point of CPR isn’t necessarily to revive a person? It’s about keeping the heart pumping, moving blood to vital organs, tagging in as an intermediary pulse until emergency services arrive. Movies made me think that CPR was only successful if a person woke up gasping, but in reality the magic of it is mostly invisible.

This winter, my friend Joel had a heart attack while on his daily bike ride through the park. He went down, a group of park volunteers found him, and two of them performed CPR until an ambulance arrived. Their effort saved his life. It was a complete and total miracle.

As I heard this story later that week, pulled into the quiet back office of the co-op, my emotions were all over the place. Devastation and knee-buckling gratitude all at once. How awful. And how lucky.

Because if you zoom out from Joel’s experience, you can’t miss the civic and relational fabric that held him in his time of dire need: he was in a public park, using a bicycle, there was a nearby club gathering people together, and they had the skills to save his life.

There’s so much to learn from this. And as a city, that’s kind of what we did.

Here’s what was happening simultaneously: a city alder – also close with Joel and feeling the fresh learnings from his experience – was in the midst of talks with her neighbor about expanding CPR education across the city. This neighbor’s work as an emergency physician focused on public adoption of CPR. (This world! It is so small!) He brought in a teaching EMT who heads community outreach across the city. (SMALL!) Then, they pitched the city manager of the New Haven Free Public Library system on hosting a series of free classes at every library branch for the public to learn CPR, Narcan, and AED.

Attending this class for me was an emotional experience. Of course I couldn’t stop thinking about Joel the whole time, as I imagine every other person in the room also thought about their loved ones and how they may need (or have already/could have been saved by) practices like CPR or Narcan. These life-saving techniques are practical, and they are also bone-vibratingly personal.

The class was short – maybe a little over an hour – and there wasn’t an empty chair in the library auxiliary room even though it was a Monday afternoon. The space was one of the most diverse I’ve ever been in; youth were there who felt it was the right thing to do, elders there for their spouses and friends, organizers and caretakers and volunteers and people just brushing up. We watched a video, learned from the trainer, and then broke up into pairs to practice CPR and using an AED device on a mannequin. The class itself doesn’t count as an official certification (one or two people walked out upon learning this) but it does give you the essential skills needed to perform CPR. Plus, I got a cool little card.

Sitting alongside everyone in that room honestly felt spiritual. To be gathered together around the importance of saving life – not because it was mandatory, not because we had to do it through work, not because it was even going to give us an official certification – was like kneeling at an altar of loving care.

“Probably for many of us, CPR is a nice-to-have,” said Caroline Tanbee Smith, the alder who helped kick off the program. “I knew it was important if I was around students or if I was going to be leading a group of first years into the woods. But after what happened to Joel, it just landed for me as something that as a neighbor, I should know.”

CPR, applied immediately, can triple someone’s chance of survival. Naloxone reverses 93% of overdoses. Bystanders are part of what’s officially titled the coolest thing ever: the Chain of Survival. Every minute that passes by after a cardiac arrest without CPR increases someone’s mortality by 10%, a fact made more dire by longer ambulance response times in low income and rural areas.

This is all a fancy way of saying: there is literally nobody better positioned than you and me to save someone’s life in the immediate aftermath of a cardiac arrest or overdose. I think I knew this, but I didn’t know it know it, and the class helped me believe.

Dr. David Yang, the emergency physician at Yale who focuses on this work, told me that bystander CPR rates are actually tracked, and in this case used as a baseline for community training. Towns around New Haven had bystanders perform CPR in 20-30% of cardiac arrest cases, but New Haven itself had a wildly low rate of bystander intervention at just 5%.

“We really needed to ramp up the amount of training we were doing,” said Dr. Yang. “It was in the ballpark of 500-600 people per year – which is a great number – but you need to get onto the level of having trained thousands of people to really see a community-level impact for our interest of survival.”

As many of us are increasingly thinking about our responsibility to each other in community life – whether it’s participating in ICE watches or distributing warming kits – this way of thinking about scale and citywide education feels especially potent.

What if we also aspired to training thousands of people across our cities in de-escalation? Speaking another language? Mental health crisis support? What else do we owe to each other, and what would it look like to achieve community education at scale?

The willingness to intervene

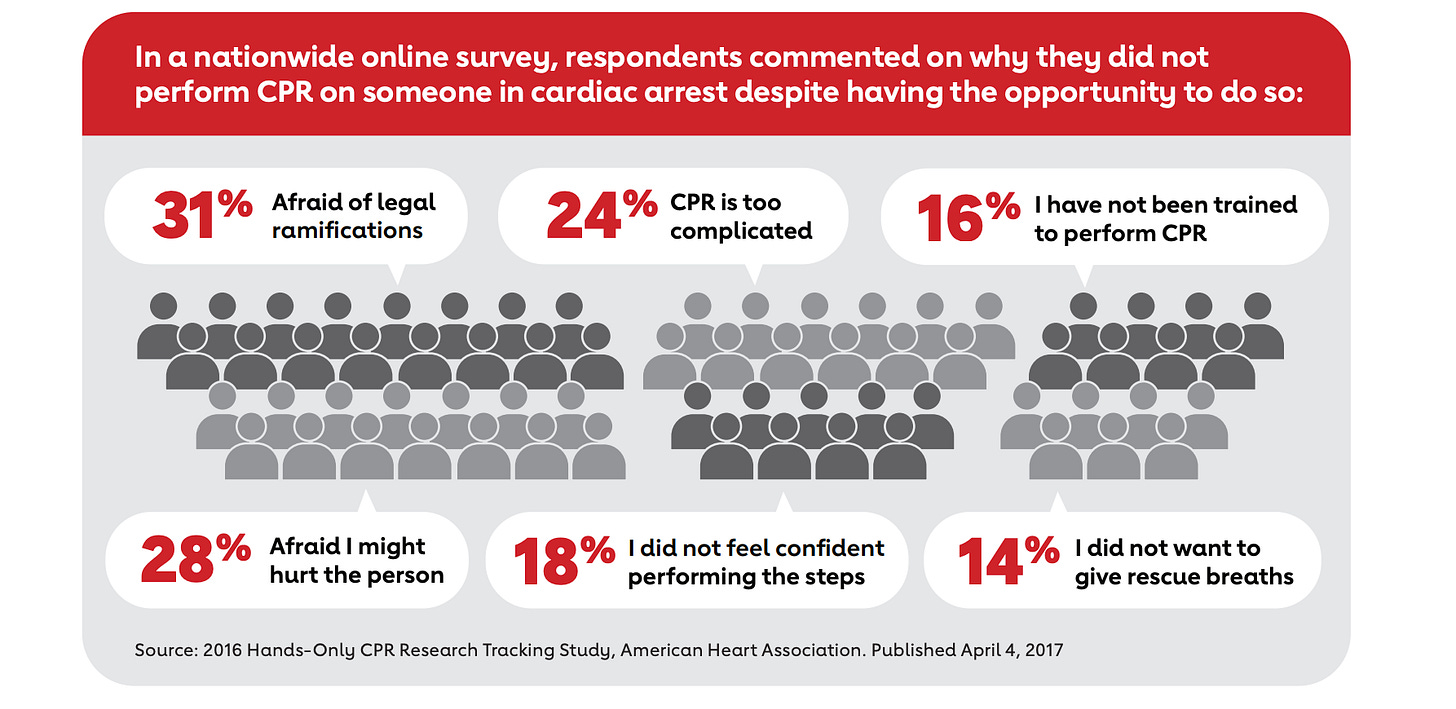

Many Bystander CPR resources have taglines like “Don’t be afraid. Save a life.” and my personal fave: “That heart’s not going to start itself.” Bystanders might not perform CPR for more tangible reasons like fear of legal ramifications or not wanting to give rescue breaths1, but there’s also the less tangible: lack of confidence, feeling like it’s ‘too complicated’, not wanting to hurt the person.

This is an issue of training, for sure, but it’s also an issue of what we’re willing to do for each other.

Willingness is a sort of magical thing. It’s about readiness, preparedness, and agentic participation, by its dictionary definitions, but it’s also about a little more than that. There’s something intangible in the gap between knowing how to do something and doing it, particularly when that something involves a stranger.

Yes, this CPR class was great because it was free, easy to understand, and offered at our local library branch. But there were also the sparkling side effects:

Bystander identity-building – It felt so clear that bystanders were essentially heroes, and we were already part of that circle by being in this room, which made me feel proud and ready. It was sort of like being in an exit row? Except obviously way more meaningful.

Everyday stories as context – Joel’s story was brought up in my class, as were other scenarios from around New Haven. This shifted the zone of imagination to the sidewalks, to our homes, to the park – forming pictures in our minds of where we should be ready to do this.

Practicing with strangers – When we went into physical practice, splitting up who called for an ambulance or got the AED ready, we did so with our classmates, aka strangers. It was awkward and stressful and exactly how it would be in real life.

My dear friend Amanda Levi shared that while she’d taken a handful of CPR courses in the past for work, “this one felt especially engaging and empowering. I feel confident I could actually help in an emergency.” Like Amanda, I first learned CPR in the context of my work at a museum because I was “around members of the public.”

What does it mean to be around the public when we are, all of us, constantly around the public? If you’re sitting on a bench at a park, aren’t you around the public? Getting coffee with a friend? In front of your apartment?

Lifesaving skills like CPR and using Narcan shouldn’t just be available to us if we’re at a museum or other context where professionals had to get certified. They should be as expected as opening a door, as a wave to cross the street, as tossing back a ball that got away.

CPR is like food assistance is like breathing with someone having a panic attack is like sewing a button on your neighbor’s beloved jacket. The jobs of a few are becoming the jobs of us all. So how do we plan to learn together?

A new GROUP HUG segment about replicating great work

Let’s break down what made this class possible, and how we might replicate parts of it in our own community contexts:

Converting an emergency into a learning. Joel’s experience was both a motivating personal connection for Caroline and a real-world, local example shared in class. How might you build on a successful story in your community and replicate its learnings?

Strong sponsorship and cross-community partnership. What made this special was a connection between an elected official, local experts, and an entire library system. Each partner added something impossible without the other. Whose relationships and expertise might support you in doing something you couldn’t do alone?

Setting goals and understanding local data. There was a baseline of bystander CPR data and a goal to increase it; Dr. Yang’s intention is to train 1,000 people a year in order to reach a greater community education saturation point. What would it look like to build on research and set specific goals for impact in your own community?

Shifting the idea that the ‘job of a few’ is actually the job of us all. The class was free, offered at different times in each neighborhood, and focused heavily on the bystander identity. How might you leverage logistics, content, and identity-shaping to build agency among a group of people?

Extra Reading + Resources

And if you’re curious about bringing a program like this to your neighborhood, reply to me here and I can connect you to folks who made this possible here :)

or simply click that ₊˚.⋆⁺₊💜₊˚.⋆⁺₊ at the top if you indeed liked it, we always appreciate that here at group hug hq!! love to you all

💸 If you enjoyed this, consider dropping a buck in the GROUP HUG hat! I’m so excited to try this new alternative to paid subscriptions (which have been paused for a while anyway) to pass support from this newsletter onto groups in my town which I clearly draw all of my inspiration from.

This class was ‘hands-only’ CPR (aka not mouth-to-mouth) which is just as effective and taught in many community education programs these days.

I love this story, Elise - thank you for sharing! It makes me think of community initiatives like the Oakland Power Project, which offers workshops focused on empowering people to deescalate emergency situations and reduce engagement with cops when seeking healthcare (acute emergencies; behavioural health; opioid overdose prevention). https://oaklandpowerprojects.org/

This is so beautiful and moving! I love this newsletter so much.

Also, “That heart’s not going to start itself” 🤠 so good