welcome to my annual “really long one”! feel free to listen to the sultry tunes of my voice if you prefer to reading many words one after another

Last year, an article came out documenting the rise of the “shoppy shop”, a.k.a. what I joke is this generation’s As Seen on TV stores except it is As Pummeled Into You By The Internet. These are the boutique cafes, mini-grocers, random nooks at clothing stores that all sell the same internet hot sauce, internet tinned fish, and internet crackers.

It’s almost like a store brand except the entire internet is the “store” so the scale of its familiarity is gargantuan. The aesthetic of the olive oil matches your chili crisp matches your pasta so you reach for it, post about it, love displaying it on your countertop. It’s something basic – pantry items – elevated to outer space and made desirable because of its aesthetic, its class signaling, the moment it shows you’re definitely in on.

The shoppy shop aura was one of those things where, once named, I couldn’t help but see everywhere else: Something in real life becoming more desirable primarily because of its presentation on the internet, and less desirable if it had none.

So what happens when that effect comes for our social spaces?

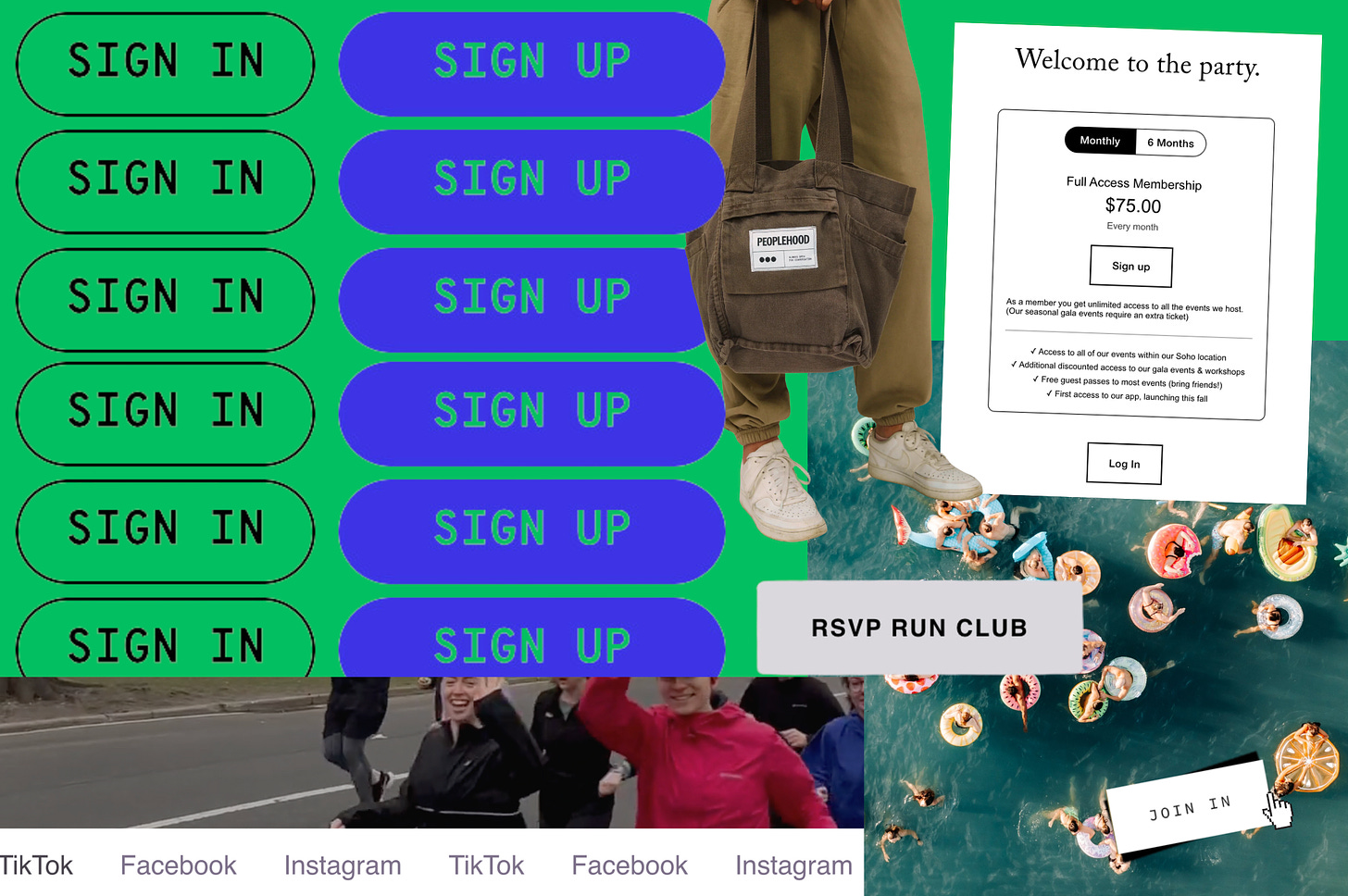

These are the run clubs and swim clubs with very robustly branded websites for some reason, websites that greet you with full-width videos of delighted people being very sweaty together. New ventures for “group conversation” or exclusive social spaces or curated clubs with sign-up flows and membership levels that evoke the rigor of a bank account registration. Book clubs with pages of merch or speed-dating startups with podcasts and constantly updated feeds. Talking clubs or dance parties with press mentions from Forbes and the New York Times listed on their front page?? This sort of thing.

It’s a format that feels familiar because it mimics the look and feel of something we might do every day: shop online. We begin to navigate social life itself the same way we might browse brands, endlessly “window shopping” meet-up groups we will never go to, or placing more trust, worthiness, and desirability in social experiences because they have…better looking websites. Or fantastic Instagram presence. Or merch!

We aren’t bad or stupid for being drawn to things like this, especially since they make up many emerging clubs or gatherings or venues these days. It is mostly cool that effort to bring people together is happening at all, and (for many legit reasons that will be explored below) it can be a wonderful thing to understand so much about a social experience ahead of time.

But because we are all so very lonely we need to stay sharp, people! Weird things will happen in order to hook our desire for belonging. I’ve written before about how one of these things can be making us pay for community through friendship boot camps, membership-based social clubs, or commercial advertising that promises relief from isolation (new entry: this very regional, very odd 99 Restaurant commercial). These are often packaged to offer a “solving for me” type of pay-to-play, but for something we all deserve for free: love, connection, and an unshakeable sense of interdependence.

Here, I want to explore this same phenomenon more from the angle of homogenized, hyper-optimized community experiences, and the ripple effects that come from what we lose when all of our communities look and feel the same. How it changes us and the world when “onboarding” into a new social space becomes increasingly slick. How it reshapes our very expectation of what a social experience’s digital footprint should look like, and shrinks what we might even consider as desirable things to go to.

This isn’t a takedown of any of the examples shared here, but intended to be an exploration of all the neuron-firing that happens when we begin to see some opportunities to find community as more attractive than others simply because they have a good logo. I want to explore it for anyone who has ever joined one of these things and come up short on the experience they were after, but felt like the odd one out since everyone else seemed to love it so much…in the pictures, at least.

I Just Want To See What It’s Like First

In the summer of 2021, newly vaccinated, new to town, and aching for closeby friendships, I scrolled.

I did that thing where you triangulate social media content with the freneticism of solving a missing persons case, hopping from the account of one person who was at one house show to the page of the house the show happened at to the band who played there back to the house’s linktree and their calendar of upcoming shows to the calendar on my phone to see what day a show would be on to streetview of the house to biking, walking, driving directions between where I lived and them. 13 minutes biking. I was free that night. The show would be outdoors. It was all the information I needed to know to go and then some.

But for some reason it wasn’t enough? I went back to the house’s feed. I watched every story they posted over the next few days, looked back at pictures they were tagged in, cringed at a jam band who played the week before. A tally had started up in my catty little cortex: that seems like a person I could be friends with. Ok nevermind that other person looks like they would insist on giving me a back rub. Every single image flew together to create a portrait in my mind about what sort of space this was.

I am, of course, describing the process of judging something on the internet. But it didn’t feel like that at the time. It felt way more like the daily dance that happened before I went anywhere during the pandemic; I wanted to know what it would be like when I was there. How many times had I looked at photos of outdoor seating at a restaurant I was considering not just doing takeout from? Or scrolled reviews looking for horror stories of anti-masking? How many times would I need to hear another friend’s story about a positive experience they had before trusting it enough to try it myself?

A lot. So so many! Every day multiple times a day.

I just want to see what it’s like first. Pretty convenient because it was one of the only things to do: look without touching, assess from afar, vibe it out before actually going.

More than any digital hangover from the peak pandemic, this craving is hardest for me to totally shake. My screen time is down. I’m off social media. But I cannot stop overrelying on digital interface as a way to sniff out experiences I’m curious about. I find myself using the same filter to look at the clogs I want to buy as I do a social thing I want to attend as I do a restaurant I want to go to. Who’s the sort of person that goes there? What is it like? Do they have an e-mail newsletter? Does it look cool? Should I go?

But how much of this really matters? Shouldn’t it just be enough that there’s a house with a show and a band I might kind of like?

There’s a section on Tripadvisor called “Need to know before you go” and I sometimes think of this body of modern information swelling to the size of an encyclopedia. I need to know everything before I go. As much as you can tell me is exactly what I need to know.

Communities with Sweatshirts and Sticker Packs

If there is a widening gap in between our desire (“I want community”) and our threshold of knowing enough (“What is it really like there?”) the thing that would fill that gap is information.

There’s the essential kind of information – where, when, cost, some context – but then there’s all the…other kinds of information. Aesthetics. Content. Vibe? Relevance. Tech.

An example I’ve brought up here before is a volunteer group that tends to the city park near my apartment. They offer all of that essential information; I know where they meet, who to contact, and even just got added to a legendary weekly e-mail update that lists who showed up and what snacks they brought each week. What they don’t have is: a logo, updated social media, merch, any sort of “sign-up flow” (I was on their official newsletter for a while but only discovered the secondary e-mail I mention above after a friend directly connected me with the organizer?), a website that is more than one page.

Contrast this with something like the Friday Morning Swim Club, a weekly Chicago meet-up where thousands of people plunge into Lake Michigan together every Friday. They’ve got a logo and playful typography, drone videos, a full About page featuring do’s and don’ts and their featured coffee, a shop full of branded hats and puzzles and prints and sticker packs. There’s a founders story and a full gallery and links out to social media where dozens of people have also made their own videos about the Swim Club.

I feel something distinct happening deep down in my most online lizard brain between these two experiences. The Swim Club feels memorable and desirable, cute and colorful and alive and FOMO-inspiring (even if my actual nightmare is being trapped in a donut floatie with one thousand other people in a lake). The happiness of it all sort of bursts through the screen and slaps you around for being crazy not to want it. I don’t have any associations with the parks group beyond the weekly photos they send of volunteers looking smiley but awkward.

Or take something like Alcoholics Anonymous. While there is a central website covering their methodology and questions about sobriety, you are redirected to dozens of different more local online sources to find a meeting near you. There are state websites and national directories and randomly curated lists that all look and operate differently from each other. It is an experience made real by its tendrils in your town, popping up at different churches or halls or on zoom. It breaks every “optimized” rule but helps millions of people find peer support in their recovery.

While there are different motivations to attend a group like this, compare again to another peer conversation space like Peoplehood. It’s a new venture by the founders of SoulCycle that offers 60-minute guided group conversation that feels “like a workout for your relationships” and was developed in part from research on groups like Alcoholics Anonymous. First: I did think Peoplehood was just clothing because of all the neutral sweatsets featured on their website. You are prompted to Sign In and Sign Up. Scroll for testimonies from members and The New York Times. Scroll again for membership pricing or buying “credits” for packs of “Gathers” and a shop where you, too, can buy all of the bread colored merch.

“We know these minimalist-ish generic aesthetics are not connected to any true local origin, but we see them as indicative of some kind of authenticity. My current thought is that they don’t feel local to a place, but instead they feel local to the internet, which is, after all, where we all live,” culture writer Kyle Chayka shares in that shoppy shop article.

How is it possible that a swim club 800 miles away manages to be more compelling than a group meeting half a mile from my door? Or a venture-funded peer group appears to have more clout than one that’s existed for 89 years?

It is about branding and aesthetics and what we actually prefer doing more, yes, but it is also about the user experience of navigating the digital platforms linked to these spaces. These might feel more trustworthy because:

Their aesthetic and experience reminds us of other things we do every day that look and feel like it – mainly shopping. They’ve got e-mail flows and merch drops, brand guides and photos, and so much fresh, daily content for social.

Good branding signals other things related to class and positionality – if an experience looks good, it’s because it was crafted at some point by a designer and a creative director who had the time, skills, and zeitgeist awareness to know what looks good (one of the founders of the swim club mentioned above is a graphic designer by trade, as an example).

“Loneliness” and “belonging” are often explicitly named as deficits to treat or offerings to make, which gives these groups a zest of hyperawareness and relevancy, fresh off the last Atlantic article about the loneliness epidemic. This is also a very specific value prop to offer (which I’d argue is another indicator that they are more likely to be venture-funded; a value prop that grabs us is the same that makes it a compelling investment)…versus something like my parks volunteer group which says nothing about addressing these gaps in our social fabric, though it definitely does.

“Touchpoints” show up where you already spend our time – our social media feeds, inboxes, mobile-friendly websites…online. Maybe not as much true word of mouth (i.e. not just seeing your friend post about it), by way of flyers on telephone poles and community boards, or stumbling upon it in person.

It looks…good?

If the only worthy social experiences of today must tick all of the boxes above, what might we miss out on? How do our expectations shift and rise?

In CAPS LOCK, Ruben Pater traces the evolution of branding from livestock to slavery to mass-produced goods. Today it has obviously gone lightyears further, grooming every part of an experience that may not even be associated with a product you can hold in your hands. He writes: “Even a well-designed brand for a museum still uses the same logic of branding to sell more tickets, more merchandise, to increase visibility, to make more profit, perpetuating the narrative that everything needs branding.”

There’s a quote he shares from designers Ellen Lupton and J. Abbott Miller about how brands "replaced the local shopkeeper as the interface between consumer and product." I wonder if something similar is happening now but with social life itself; brands replacing community organizers as the interface between participants and experience.

What We Lose

So what happens when the bar is raised for what makes a community experience trustworthy, frictionless, consumable – or in another word, desirable?

The zone of viable community experiences shrinks. If desirable = active social media presence and a crisp logo, this just naturally excludes so many events, meet-ups, and groups that fall outside of that criteria. We may feel like there is “nothing going on” even though there is, it just may not have an optimized digital footprint. We may not hear about it on social. We don’t have the patience to navigate their bad website.

It may be more likely to be pay-to-play. Design takes time and effort. Content creation takes time and effort. Everything that goes into a shiny digital footprint – website design, hosting, platform service subscriptions – costs money. Compare this to a random book club meet-up advertised through a single flyer made by hand and stapled to a few telephone poles. On the other side of all the infrastructure it takes to create a beautiful digital presence, there may be a greater likelihood of subscription models or fees that support the efforts of organizers. (Time and effort they should be paid for, to be clear! Membership dues are a vital source of support with a long legacy. Just saying that it’s a different threshold of experience than something more scrappy, distributed, or volunteer-run.)

Starting these things feels less possible for just anyone to do. If every community needs a logo and you can’t afford a squarespace or want to post on Instagram five times a week, are you allowed to start your own thing? Do you need a team just to start a gardening meet-up?

More grassroots – and possibly more impactful – efforts feel less trustworthy. There is a community fridge in my city that has existed since 2021 and has a basic social media presence. But it isn’t updated often, and I find myself having a “huh maybe they’re not active anymore” assumption even though a) they posted 2 months ago and b) I could simply go there in person or contact an organizer to see. This work is intensive, and variable, and volunteer-run, and thus maybe less likely to offer a minute-by-minute update on a new chard donation that just dropped. Why would that convey less legitimacy? If the bar for being “active” is set at a pace that means you are forgotten or defunct if not posting on the internet daily (even as you continue doing real work in the real world), it may leave vital community work or more volunteer-run efforts in the dust.

We lose the feeling that comes with a little mystery and a healthy amount of risk. When we don’t know exactly what’s going to happen, you know what happens? We get to be surprised. Our anticipation builds in the not knowing – better get there early to figure out getting in, ask others if it’s their first time, scan a pamphlet for clues or read seating arrangements like tea leaves for a sense of what’s about to happen – and it transforms our sense of payoff in the experience itself. It makes the whole thing sweeter. To know it all also robs us of that special sense of timelessness when doing something for the first time; I’ve noticed a hyper-presence in myself when I’m not counting down time until the next agenda item, or when I don’t even know what the next item is. This isn’t to totally glorify the not knowing; we each have our own distinct thresholds for what “essential information” we need before going somewhere. Maybe not knowing sounds like your nightmare, and for good reason. But I know I’ve found my threshold for information rising even as I wish it didn’t, or missed out on the texture of the mystery completely because I had to watch someone’s play-by-play of a biking event or meet-up.

We miss out on good friction. When I recently showed up to a dance class for the first time, I had no idea how to actually get into the building. But there were people outside also wearing tights and slouchy socks, and I asked them, and then I got to help someone else who didn’t know, and then we all rode up in the elevator together talking about how nervous we were. None of these interactions – which made me feel more at ease – might have happened if I had a perfect, frictionless sense of exactly how it was supposed to work. Good friction means we have to rely on other people to figure it out.

To make a caveat for the fortieth time because I’m terrified of lost nuance on the internet: a great website and active social media presence does not mean community is being “done wrong” and we aren’t failing by wanting to know as much as we can to be comfortable. And I don’t want to pedestalize every experience with no upfront information. It is crucial to know if you can physically access a space, for example, or will be able to participate in an activity, or are prepared for the type of content that might be explored. It can also be a matter of safety to assess ahead of time if these are your sort of people; will we feel seen, held, and joyful where we are going? Social media is a gift to these questions because it lets us peek in to exactly how it might be.

Earlier I mentioned “essential information” versus all of the other stuff – aesthetics, tech, tone – that has begun to feel as essential as a time and place to meet. Maybe what I’m wondering is if there can be something in the space between these two poles; good things to borrow from the expertly branded experiences, and healthy things to release, modeled by all of the scrappy community projects, low-tech legacy institutions, and grassroots efforts with spotty as hell instagram presence.

Organizations like New_ Public are already exploring this in-between space, whether by studying print community newsletters to inspire digital alternatives, conducting extensive research into legacy networks like Vermont’s Front Porch Forum to learn what makes it a more generative online space for neighbors than sites like NextDoor or Facebook, and offering resources for anyone to use in cultivating their own digital public spaces. Their belief that “if digital products and services utilized less extractive business models and were designed to be more prosocial, this would lead to more public-spirited, positive offline outcomes” feels like the balance I’m craving in tech mediating social life.

I also can’t help but think of so many stories from the communities affected by Hurricane Helene and Milton; how in the absence of internet, power, and basic services, we do need to find our ways to each other as a means of survival. In the mass of devastating news and firsthand account videos, the stories about river raft guides leading search-and-rescue efforts or neighbors conducting wellness checks or local restaurants offering hundreds of free meals always brought me to tears and inspired awe in the comments. Yes, because these were heartwarming stories in the midst of so much heartbreak, but I wonder if it is also because it demonstrates a type of remembering that we are still very much capable of – when we have to be.

As I try to unlearn the taste for a hyper-branded, hyper-optimized community presence, I’ve been asking myself some questions:

What essential information do I need to know in order to check something out?

Can this body of information be smaller?

Do I want to go to this thing or does it simply have a cool logo?

What feelings come up in me when I feel like I don’t know enough about something to go? Why? What feelings come up when I see a well-documented social thing on the internet? Why?

What experiences have I been “meaning to go to” but haven’t? Why? (Sometimes I notice this might be because there is too little information, or maybe so much information it keeps me suspended in window shopping.)

Is there a friend or actual human being (e.g. organizer, coordinator listed somewhere) I can get in touch with directly to ask what I want to know?

And as an organizer of experiences for others:

What are my influences?

What other platforms – online or in-person – exist beyond the mains of website and social? (i.e. text groups, telephone poles, local newsletters)

How might I give more information about accessibility and navigation up front?

Is a certain expectation of “quality” or user experience holding me back from doing anything at all? What is the ugliest, lowest tech version of this that can just be tried?

Does this need to look cute or just be functional?

As organizers, let it be friction-ful or not cute. Let it be functional and clear but maybe ugly. As participants, let us widen our zone of comfort with organizations or groups who have ancient facebook pages or websites where you aren’t sure where you even put your e-mail address. Maybe we trust them more because they’ve managed to keep going in real life…without optimizing the internet.

or simply click that ₊˚.⋆⁺₊💜₊˚.⋆⁺₊ at the top if you indeed liked it, we always appreciate that here at group hug hq!!

I appreciate this piece so much. As someone who recently stepped into overseeing communications for a hyper-local, grassrootsy nonprofit with "building community" in its mission, this productively challenged some of my assumptions or mental shortcuts about what "good" or "professional" communications should look like. ("Look like" being the operative word there.) Effective and inclusive communication, yes, but glossing everything into optimized homogeneity, not so much.

Loved this. So thought-provoking. Thanks for sharing.